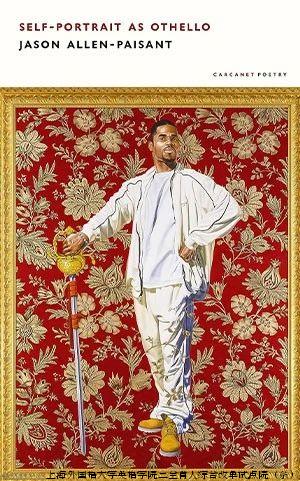

值此莎士比亚诞辰460周年之际,苏以宽老师为英华读书人推荐了牙买加诗人詹森·艾伦·佩桑特(Jason Allen-Paisant)的获奖诗集《奥赛罗自画像》(Self-Portrait as Othello)。苏老师将带我们通过佩桑特独特的视角和细腻的笔触,将莎翁笔下奥赛罗的经历与现代欧洲黑人移民的现状紧密联系起来,并由此深入思考人性的复杂性以及社会中不同群体的命运与挣扎。

Self-Portrait as Othello

by

Jason Allen-Paisant

苏以宽

上海外国语大学英语学院讲师,硕士生导师,上海市“晨光计划”学者。

更多荐书者信息访问:

http://www.english.shisu.edu.cn/_t8/e2/2d/c10882a123437/page.htm

In the opening act of Shakespeare's Othello (1603), Iago instigates racial animosity by telling Desdemona’s father, Brabantio, “Even now, now, very now, an old black ram is tupping your white ewe,” (1.1). This line epitomizes the play's racial tensions, as Iago uses charged metaphors, like “black ram” for Othello and “white ewe” for Desdemona, to evoke stereotypes and dehumanize Othello with terms like “a Barbary horse” and “an erring Barbarian” (1.1, 1.3). Roderigo reinforces this prejudice, calling Othello “the thicklips” (1.1). Othello’s origins from the culturally distant Barbary region accentuate his "otherness," marking him as an outsider in Venice, despite his efforts to assimilate. This perception of Othello as mysterious and exotic fuels the hostile reception he receives from Venetian society.

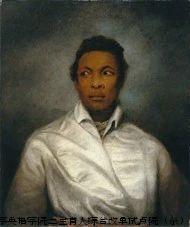

Ira Aldridge as Othello, the Moor of Venice,

by James Northcote (1746–1831)

at Manchester Art Gallery

It is within this context of otherness and racial prejudice that Jason Allen-Paisant's Self Portrait as Othello (2023) engages with Shakespeare's play, providing a contemporary reimagining of the character’s narrative. By focusing on the missing backstory of Othello, Allen-Paisant not only breathes new life into a perennial character but also forges strong connections between Othello's experiences and the modern-day realities faced by Black male immigrants in Europe. This approach allows the work to serve as a bridge between the past and present. Allen-Paisant's background and personal journey deeply inform his reinterpretation of Othello. As a Senior Lecturer in Critical Theory & Creative Writing at the University of Manchester, his academic expertise is blended with a sense of scholarly insight and creative expression. Born in Jamaica, Allen-Paisant's relocation to the UK in 2011 to pursue a DPhil in Medieval and Modern Languages at Merton College, Oxford, mirrors the journey of many immigrants. This personal experience of migration and adaptation infuses his exploration of identity, belonging, and the complexities of assimilating into a new culture with a layer of authenticity and emotional depth, all while bearing the weight of one's original heritage.

This innovative approach contributed to the collection winning the prestigious T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry in 2023. Established in 1993, the prize honors T.S. Eliot’s legacy by celebrating outstanding poetry published in the UK and Ireland, and it supports poets with a significant monetary award, fostering a platform for diverse voices and challenging systemic inequalities in society:: Roger Robinson's A Portable Paradise (2019), Bhanu Kapil's How to Wash a Heart (2020), Joelle Taylor's C+nto & Othered Poems (2021).

By situating his work within this lineage, Jason Allen-Paisant's Self Portrait as Othello stands out as a pivotal piece in the ongoing effort to decolonize the literary canon, destabilizing the predominance of white hegemony. Allen-Paisant inherits and advances the resistance against marginalization, marking another milestone in the journey towards a more inclusive literary representation. His work seeks to dismantle the Eurocentric perspectives through postmodern deconstruction. Self Portrait as Othello is more than a literary homage; it is a critical intervention that questions and expands upon the narrative spaces left vacant by Shakespeare. Allen-Paisant’s choice to connect Othello’s story with the contemporary experiences of Black immigrants compels readers to reconsider the historical impacts of race and migration in Europe. This in turn implicitly critiques the romanticization and vilification of the “otherness” in literature and society, urging a deeper empathetic understanding for the multidimensional struggles of Black individuals in domineering white spaces.

In the opening stanzas of the collection, the poem crafts a tender dialogue between the storied figure of Othello—a distinguished Venetian aristocrat and African warrior—and his beloved. She, transcending the confines of her societal upbringing, dares to dream of a shared future with him, unswayed by her father's stern disapproval:

Self-Portrait as Othello I

Undeterred by father’s anger

& disapproval,

she thinks that we

should have every right

to be in love—

Venice aristocrat,

African soldier.

Her belief,

this version of myself,

a future

for her and for me—

why should I always fight?

Raised by tales of Barbary

and Guinea, she offered her country

in exchange for my stories—

encounters with death,

my childhood as soldier

on the River Gambia.

The jealous white boy’s venom

was language—

even now very now

an old black ram is

tupping your white ewe.

When I spoke, my sound

was white gaze—

proving I was just as good

& everything was done

to remind me these rules will never

make you forget—

the very real thing

is that you should not have

too much, should not be

too large in this space.

What is Iago but that—

the language controlling the play.

And what he was saying,

thousands were saying and thinking.

Here I am now; we see

how it ends; yes,

we’re freed from the play.

As faith crumbled

I thought, probably

you loved my storytelling

more than me, Mandinka warrior

da Ghinea;

and the demon became

my own face.

And still—dare I believe

that this was real?

Is there chance for revision?

Do we enter the stage

in another world?

Do we continue

our unfinished rehearsal?

This relationship, set against the backdrop of racial and cultural prejudices, seems to echo Frantz Fanon’s discussion of the Black individual's struggle against the inferiority complex imposed by a white supremacist society: “The colored man enslaved by his inferiority, the white man enslaved by his superiority alike behave in accordance with a neurotic orientation” (Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 1986, p. 63). This perspective reveals the tragic love story of Othello as more than just a personal saga; it serves as a political critique of the societal standards that determine who is considered worthy of love and belonging. Othello's descent into jealousy and mistrust further highlights the neurosis induced by systemic racism.

Othello's introspective soliloquy, “What is Iago but that— / the language controlling the play,” signifies a pivotal moment of self-awareness, wherein Othello becomes cognizant of the extent to which his fate is intertwined with the linguistic manipulations of Iago. This moment of enlightenment is emblematic of Othello’s entrapment within a narrative framework that is deeply entrenched in racial hierarchies. Such a narrative framework not only dictates the dynamics of power and identity within the play but also mirrors the societal constructs beyond its fictionality. This insight into the mechanics of his manipulation aligns with Frantz Fanon’s theoretical discourse, particularly his argument that the identities of Black individuals are invariably molded under the pervasive scrutiny of a white gaze—a gaze that ceaselessly casts them as lesser or the “other.” The poem intimates that such a revelation does not free Othello; rather, it propels him towards a more profound assimilation of racial biases, recognizing the "demon" within himself.

These lines further explore the complexities of the speaker's colonial-based identity, referencing the Barbary, Guinea, and Gambia rivers, and connects personal history to the larger cultural narrative. The poem describes the speaker's negotiation of identity in a colonial world, criticizes language as a tool of oppression, and exposes power dynamics inherent in a society established by hegemonic discourse. As the narrative wades through the metatheatrical dimensions, it condenses the essence of performance—not just on stage, but in the lived experiences of the character. Here, the heart of the piece beats loudest, in its tender grappling with the shadows of history and the luminous power of memory to both revive and transform, painting the stage where Othello re-emerges, not just as a character, but as an enduring spirit wrestling with the chains of historical injustices.

The form of the sequence further informs its content. The syntax is notable for its use of enjambment, where sentences and phrases flow beyond the lines and stanzas, creating a sense of continuity and momentum that mirrors the ongoing nature of the speaker's journey and struggle. Furthermore, the stanzas are varied, with sections divided into smaller, focused segments of three lines. This mirrors the poem's tonal shifts—from personal aspirations to the societal constraints imposed by the historical weight of the speaker's identity.

Transitioning from Othello's persona to the broader narrative of the Black immigrant experience, Allen-Paisant's “self-portrait” of Othello as a metaphorical figure underscores the multifaceted racism and alienation that transcend historical periods and geographical boundaries. By drawing parallels between Othello's narrative and the lived realities of Black African immigrants, the lines seem to illuminate the ongoing issues of racial alienation, and the quest for identity and belonging in environments that frequently marginalize and devalue Black bodies:

Self-Portrait as Othello II

The Black body is signed as physically and psychically open space… A space not simply owned by those who embody it but constructed and occupied by other embodiments. Inhabiting it is a domestic, hemispheric… transatlantic… international pastime. There is a playing around in it.

Dionne Brand, "A Map to the Door of No Return"

You left home for

a wondering lust

for pain

had driven you

to the edge of yourself

and wanting to open the windows

of life

you decided

to migrate to this country

leaving job behind

becoming student again

to fulfil a lifelong ambition

This excerpt from Dionne Brand's “A Map to the Door of No Return” explores the concept of the Black body as an “open space,” a powerful allegory for the ways that people of colour are perceived and analysed by others. Because of the affinity with Othello, Allen-Paisant brings attention to the ongoing struggles faced by Black African immigrants. Despite coming to Europe in quest of better opportunities and integration, they frequently encounter institutional barriers and a lingering sense of alienation.

The correlation also encompasses the notion of the Black body as a “physically and psychically open space,” evoking images of voyeuristic exploitation that resonate deeply with both Othello and Black African immigrants. Their experiences, filtered through pervasive cultural preconceptions, result in identities that are more a reflection of external biases than of their own selves. This duality of being hyper-visible in terms of racial diversity yet invisibly complex in individual humanity renders a paradoxical struggle against dehumanization.

Get Out (2017)as a poignant contemporary reference that highlights a long history of injustices against African bodies.

This theme of external control and the production of Black identity under the gaze of a dominant culture echoes the chilling narrative found in Jordan Peele’s psychological horror film, Get Out (2017). Peele unwraps the layers of racial tension and objectification of the Black body. The film's depiction of Black characters going through a world that seeks to control and redefine their very essence serves as a modern allegory for the colonial exploitation of African bodies and the contemporary marginalization of Black immigrants in Europe. In Get Out, the protagonist's body and mind become the ultimate battlegrounds for his identity. Their bodies are not their own but are instead subjected to the whims and fantasies of those who view them through racial stereotypes.

The historical caricature of Black individuals as lesser beings has contributed to a coercive culture of surveillance. Going back to the 19th century, the English Victorian Scottish anatomist Robert Knox, who in popular lectures and writings regarded black people with loathing: “Look at the Negro […] Is he shaped like any white person? Is the anatomy of his frame, his muscles, or organs like ours? Does he walk like us, think like us, act like us? Not in the least. What an innate hatred the Saxon has for him!” These antiquated viewpoints share unsettling similarities with current issues, such as anti-Black police violence, which can be viewed as a modern extension of the “black peril” ideology. The historical portrayal and treatment of Black men as threats to public safety and morality directly inform the contemporary understanding of racial profiling, police violence, and the wider societal insistence on controlling Black bodies.

In the next sequence, Allen-Paisant continues his own introspective journey with the story of Othello, creating a reflective mirror between personal identity and Shakespeare’s tragic character. By invoking Othello's struggle with acceptance in a society that judges him by his skin colour, Allen-Paisant parallels these themes with his own experiences of self-discovery:

Othello Walks

Othello walks through

the marbled city;

his skin betrays him.

I am not what I am.

He is striving against

badmind. This is Othello’s life—

trying to beat the odds

and what is asked of him?

To be more fair than black

If virtue no delighted

beauty lack—

a body

just an envelope

bearing no mark

†

Where are you from &

why are you so far away

from your country?

†

You’re real to me as I

ring your name; more present

than the living. I imagine what

may have brought you to this city.

In one scenario, you’re following

your father’s

footsteps across the oceans.

You’re looking for him in the wind.

This sequence depicts a social landscape filled with complex racial dynamics. The harsh statement "his skin betrays him" serves as a thematic anchor that expresses the social judgments and prejudices that influence Othello's experiences. The refrain "I am not myself" contains an internal conflict against the dominant view of "evil" and explains the burden of society's expectations placed on individuals. This internal struggle becomes symbolic of Othello's attempt to break the dominance imposed by a world based on racial difference. To metaphorically describe the body as an "envelope" is to reduce the self to a superficial display that lacks recognition of its intrinsic value and personal complexity. The poem’s symbolic interlude, marked "†\", evokes reflection on origins, emphasizing the significance of displacement from cultural roots.

Othello's quest for family and ancestry becomes the focus of his ongoing identity discovery. Othello, following in his father's footsteps, crosses the sea and turns into a seeker of family ties in the untouchable winds as the poem expertly employs symbolism and metaphor. This creative meditation shows Othello more as memories and thoughts than as a living person. Using Othello as a moving allegory to highlight the difficulties of undergoing a world formed by racial stereotypes, this poem delivers an incisive social commentary and reclaims his narrative from the margins, presenting it as a powerful tool through which we can tackle today's societal challenges.

Recommended further readings:

Ato Quayson and Ankhi Mukherjee, Decolonizing the English Literary Curriculum (2023)

Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016)

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1952)

Mojúbàolú Olúfúnké Okome and Olufemi Vaughan, Transnational Africa and Globalization (2011)

Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Decolonising the Mind (1986)

Raymond Fancher. “Francis Galton’s African Ethnography and Its Role in the Development of His Psychology.” The British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 16, no. 1, 1983, pp. 67–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4026094. Accessed 23 Feb. 2024. 69

Toyin Falola, The African Diaspora: Slavery, Modernity, and Globalization (2013)

我要评论 (网友评论仅供其表达个人看法,并不表明本站同意其观点或证实其描述)

全部评论 ( 条)